Types of Feedback

In network externalities, two types of feedback generally known are of

- Positive feedback and

- Negative feedback

Positive feedback

Positive feedback makes the strong get stronger and the weak get weaker, leading to extreme outcomes i.e. dominance of the marketplace by a single firm or technology. Positive feedback illustrates that success beget success and failure breeds failure. In its most extreme form, positive feedback can lead to a winner-take-all market in which a single firm or technology vanquishes all others

Negative Feedback makes the strong get weaker and the weaker get stronger, pushing both towards a happy medium. For example, the industrial oligopolies exhibit negative feedback.

Positive network externalities exist if the benefits are an increasing function of the number of other users. Negative network externalities exist if the benefits are a decreasing function of the number of other users.

Sources of Positive Feedback

Supply side economies of scale

- Declining average cost

- Marginal cost less than average cost

- Example: information goods

Demand side economies of scale

- Network effects – In general: fax, email, Web

- In particular: Sony vs. Beta, Wintel vs. Apple

- Negative feedback :- In a negative-feedback system, the strong get weaker and the weak get stronger ,larger firms became burdened with high costs, while smaller firms found profitable niches

Positive feedback translates into rapid growth: – virtuous cycle. When two or more firms compete for a market where there is a strong positive feedback, only one may emerge as a winner. Economists say that such a market is TIPPY, meaning that it can tip in favor of one player or another.

The biggest winner in the information economy, apart from consumers generally, are companies that have launched technologies that have been propelled forward by the positive feedback.

Demand-side economies of scale

Traditional economies of scale is referred to as supply side economies of scale as larger firms such as General Motors, tend to have lower unit costs of production as compared to the smaller companies. Positive feedback, based on the supply side economies of scale limits the total market dominance and at that point, negative feedback begins. These limits arose out of the difficulties of managing enormous organizations where smaller companies with efficiency and superior technology ignite the positive feedback.

In the information economy, positive feedback has appeared in a new, more virulent form based on the demand side of the market, not just simply supply side. For example, Microsoft’s dominance is based on the demand side economies of scale. Microsoft’s customers value its operating system because they are widely used, the de facto industry standard. Rival operating systems just do not have critical mass to pose much of a threat. Unlike the supply side economies of scale, demand side economies of scale do not dissipate when the market gets large enough: more and more users uses Microsoft product, more incentive for others to use it too

Fig

In a virtuous cycle, the popular product with many compatible users becomes more and more valuable to each user as it attracts even more users.

For example, Lotus 1-2-3 with its superior performance, have the largest installed base of users among spreadsheet programs by the early 1980s. As PC become more faster and more companies appreciated the power of spreadsheets, new users voted overwhelmingly for Lotus 1-2-3, in part so they could share files with other users and in part because many users were skilled in preparing sophisticated Lotus macros. This process fed on itself in a virtuous cycle.

In a vicious cycle, the product loses its value as it is abandoned by users and switch to other compatible products. For example, VisiCalc, the pioneer spreadsheet program for PC, was stuck in a vicious cycle of decline. Unable to respond quickly by introducing a superior product, VisiCalc quickly succumbed.

Critical Mass and Industry takeoffs

• When network externalities are strong, a large proportion of consumers may not be willing to purchase a good unless the number of existing users exceeds a threshold network size

• This leads to the critical mass effect, a sudden rapid increase in the network size. Critical mass effects change the quantity demanded over time of a good with network externalities. The quantity demanded grows slowly until critical mass is reached; once reached the quantity demanded suddenly explodes

figure

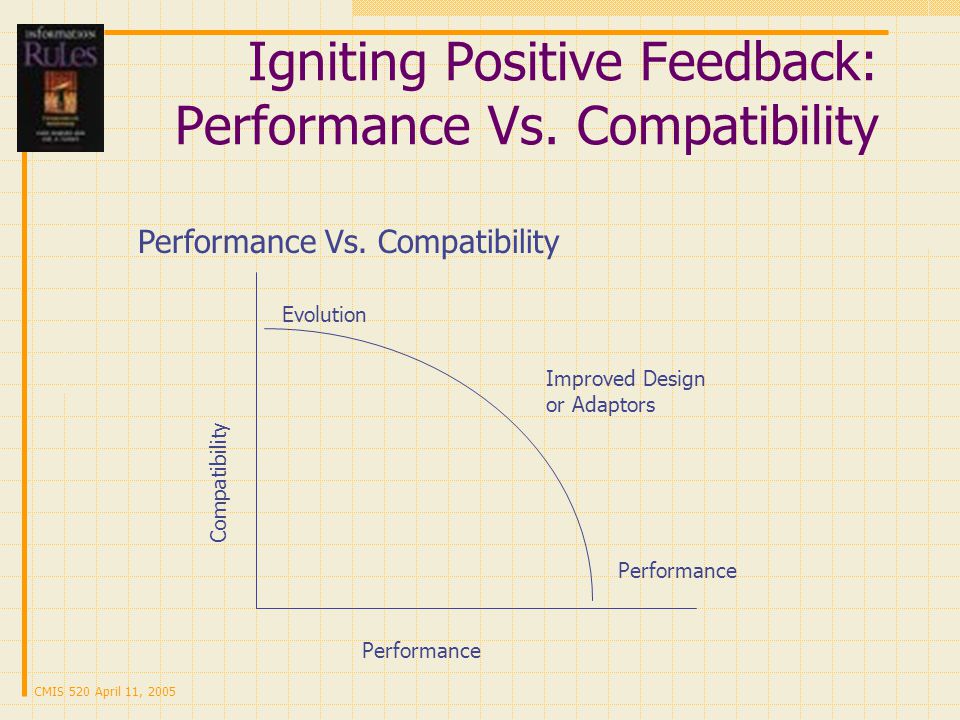

Igniting positive feedback performance vs. compatibility

There are two basic approaches for dealing with the problem of consumer inertia

- evolution strategy of compatibility

- Revolution strategy of compelling performance

The evolution strategy gives up some performance to ensure compatibility, thus easing consumer and offers a smooth migration path. High compatibility with limited performance improvements characterizes the evolution approach.

The revolution strategy offers compelling performance. Improve performance at the cost of increasing customer switching cost or vice versa. An outcome of little or no compatibility but sharply superior performance characterizes the revolution approach.

Evolution: Offer a migration path

When compatibility is critical, consumers must be offered a smooth migration path to a new information technology by reducing switching costs.

In virtual networks, the evolution strategy of offering consumers a migration path requires an ability to achieve compatibility with existing products. In real networks, the evolutionary strategy requires physical interconnection to existing networks. In either case, interfaces are critical. The key to the evolution strategy is to build new network by linking it to the old one.

The risk associated with this evolutionary strategy is that competitor may try a revolutionary strategy for its product. Compromising performance to ensure backward compatibility may leave a door open for a competitor to come up with a technologically superior product. For example. DBase vs. Access

Obstacles of Evolution

Technical Obstacles

Technical Obstacles means the need to develop a compatible technology that is superior to the existing products so that customer switching costs can be minimized, by offering backward compatibility with improved performance. For example, Microsoft’s Window 95 run old DOS applications, Office 97 reading file format of Office 95. –

The following three strategies are followed to overcome the technical obstacle in smooth migration to new technologies. • Use Creative design • Think in terms of system • Converters and bridge technologies

Strategies for smooth user migration paths to newer technologies

Use creative design

- Good engineering and product design can greatly ease the compatibility/performance trade-off

Think in terms of the system

- User cares with whole system despite the fact that we manufacture one component

Consider converters and bridge technologies

Example :- Purchase of digital signal converters by analog TV owners for compatibility of HDTV technology

Revolution: offer compelling performance

Revolution strategy involves brute force: Offer a product so much better than what people are using that enough users will bear the pain of switching to it

First attracting customers who care the most about performance and working down from there to the mass market

Compiled

Trick :-

- Offer compelling performance to first attract pioneering and influential users,

- then use this base to start up a bandwagon propelled by self-fulfilling consumer beliefs in the inevitable success of your product

HDTV set manufacturers are hoping to first sell to the so-called vidiots, those who simply must have the very best quality video and the largest TV sets available

If the market is growing rapidly, or if consumer lockin is relatively mild, performance looms larger relative to backward compatibility

Revolution strategy is inherently risky.

- It cannot work on a small scale

- Difficult to tell early on whether your technology will take off or crash

So, it is better to start off slowly and accelerate from there

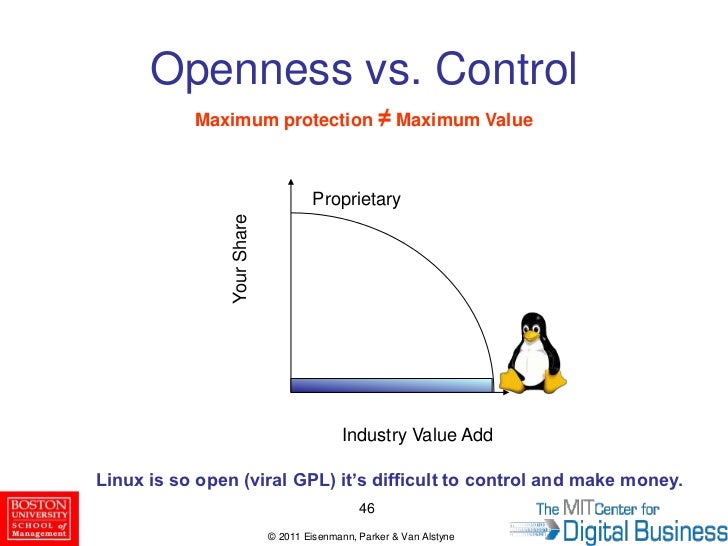

Igniting positive feedback: openness vs. control

Another fundamental trade-off is to choose an “ open ” approach by offering to make the necessary interfaces and specifications available to others or to maintain control by keeping the system proprietary.

Proprietary control will be valuable if product or system takes off and the value of network can be raised by controlling the ability of others to interconnect with the existing network. The best strategy, whether openness or control, to follow depends upon the strength of igniting the positive feedback. The strength in network markets is measured along three primary dimensions: existing market position, technical capabilities, and control of intellectual property such as patents and copyrights.

However, there is no one right choice between control and openness. A single company might well choose control for some products and openness for others. For example, Intel has maintained considerable control over the MMX multimedia specifications for its Pentium chips. At the same time, Intel promoted new, open interface specifications for graphics controllers, its Accelerated Graphics Port (AGP). Thus, Intel followed the control strategy for MMX, but openness for AGP.

In choosing between openness and control, the ultimate goal is to maximize the value of technology, not to control over it.

Your reward = total value adds to industry x your share of industry value.

Strategies to achieve openness emphasis on the total value added to industry. Value added to industry depends on Product and Size of network.

• Strategies to achieve proprietary control emphasis to the share of industry value and Industry share depends on its openness.

The fundamental trade-off between openness and control is shown in figure below. Out of the two extremeness, choose the optimal value that maximizes the total reward

Openness arises naturally when multiple products must work together, making coordination in product design essential. Within the openness category, there are full openness strategy and an alliance strategy for establishing new product standards.

- Under the Full openness strategy, anybody can make the product complying with the standard, whether they contributed to its development or not. The underlying problem is there is no champion.

- Under an alliance approach, each member of the alliance contributes towards the standard, and in exchange, each is allowed to make products comply with the standard. The underlying problem is to hold these alliances together

Control strategy is best suited to those who hold the strongest position to exert strong control over newly introduced information technologies. For example, AT&T, Microsoft, Intel, TCI and Visa all follow the control strategy. If several companies try this strategy, it may lead to standards wars.

Generic strategies in network market

1. Performance play

It is the boldest and riskiest of the four generic strategies that involve the introduction of a new, incompatible technology over which the vendor retains strong proprietary control.

Example

a) introduction of Nintendo Entertainment System in mid 1980s

b) VS Robotic with the palm pilot devices

c) Iomega with the zip drive

Performance play strategy is most attractive

- If primary advantage is based on the development of a striking new technology that offers users substantial advantages over existing technology.

- To firms that are outsiders, with no installed based customers because new entrants and upstarts with compelling new technology can more easily afford to ignore backward compatibility and push for an entirely new technology.

2. Controlled Migration

In controlled migration, consumers are offered a new and improved technology that is compatible with their existing technology

Example

a) Windows OS and Intel chipset.

b) Pentium

c) Upgrade and updates of software programs, like the annual release of TurboTax by Intuit. Such upgrades are offered by a single vendor, they can read data files and programming created for earlier versions and rely on many of the same skills that users developed for earlier versions

If you have secured domination in your market, you can introduce the new technology as a premium version of the old technology, selling it first to those who find the improvements most valuable. Controlled migration often is dynamic form of the versioning strategy.

3. Open Migration

Open migration is very friendly to consumers: the new product is supplied by many vendors with compatible technology and requires little switching cost.

Example

Multiple generations of modems and fax machines, each generation conforms to an agreed-upon standard communicate smoothly with earlier generations of machines. Open migration makes the most sense if your advantage is primarily based on manufacturing capabilities. In total case, you will benefit from a large total market and an agreed-upon set of specifications, which will allow your manufacturing skills and economies of scale to rise.

4. Discontinuity

It refers to the situation in which a new product or technology supplied by many vendors and is incompatible with the existing technology but is available from multiple suppliers.

Example

- CD – audio system

- 3 ½ “FD

It favors suppliers that are efficient manufacturers (in hardware) and that are best place to provide value added services or software enhancement (in software).